The Written Word and the Moral Nobility of Gandhi's Letter to Hitler

From Expert, To Evil

To kick off our essay-writing contest, some thoughts on the written word and moral nobility of a futile gesture

From Proficient, To Evil

To kick off our essay-writing competition, some thoughts on the written discussion and moral nobility of a futile gesture

November. 10, 2016

What could Mahatma Gandhi take been thinking when, on the eve of World War II, he typed a brief plea to Adolf Hitler, importuning his "friend" not to fix Europe ablaze? Did he really believe a seven-line letter, barely sufficient to fill a postcard, would provoke a change of heart in a man plotting the violent domination of an entire continent? Did he think the tone of his missive, deferential to the point of obsequiousness, would appeal successfully to the Fuhrer'due south titanic ego? Peradventure Gandhi, already lionized by millions of his countrymen, was so convinced of the force of his own charisma that he presumed he could change the grade of history with a quick note, dashed off in the bunting of a dubious humility. Perchance, to take the carper'southward view, the correspondence was an human action of pessimism itself; a perfunctory, un-spellchecked intonation of protest to be registered and ticked on a to-do list.

Of course, only as Gandhi could not have known on July 23, 1939 the magnitude of the horror Hitler would unleash over the next half-decade, neither can nosotros be certain of the nature of Gandhi's intentions and expectations in sending that letter. All we have is history. And every bit history had it, the letter of the alphabet never reached its recipient, having been intercepted by the British authorities, a mutual foe—it bears mentioning—of Hitler and Gandhi both. Few are then naïve as to speculate that it would accept made a whit of deviation if Hitler had actually received the note, his diabolical ambitions beingness what they were. Merely as likely, Hitler would not have been moved by sympathy for the persona and political stature of its writer. In a 1938 meeting with Lord Halifax, Hitler had proposed that the British Empire curtail the agitations of the Indian National Congress in a straightforward manner, by assassinating Gandhi. Whatever counterfactual scenarios nosotros may at present entertain inside the spacious condolement of nearly fourscore years' hindsight, the pertinent reality is this: mere weeks subsequently Gandhi posted his letter, Hitler'due south forces invaded Poland and, as Gandhi had put so concisely, "reduced humanity to the roughshod state."

The nominee of ane of the ii major political parties conducted a presidential campaign whose messaging consisted primarily of outlandish, impulsive tweets and the amplification of toxic slurs from fringe nationalists. The other side'south standard bearer squandered an inordinate corporeality of energy grappling in the gutter with her opponent, or pandering to unconvinced constituencies with vapid memes and slogans of her own.

Then what are we at present to make of this apprehensive antiquity of failure, at present that both its writer and its intended reader are long dead, their memories respectively exalted and deplored, each reduced to broad stroke metonyms for good and evil? Is it nothing but a marvel? The respond to a trivia question? A point of departure for a flying of fancy on an well-nigh-interaction betwixt a dichotomous pair of historical caricatures? The artist Jitish Kallat posits that Gandhi's letter has much more to tell us nearly ourselves and our civilization than its few meek sentences announce. In his 2022 installation Covering Alphabetic character, Kallat exhumes the correspondence from its historiographical catacomb and transubstantiates it into something at one time dreamlike and tactile, lambent and shadowy, enveloping and ephemeral. Encountering Covering Letter, one enters a darkened corridor illuminated but by the projected image of Gandhi's letter scrolling forth the floor and up the length of a screen at the far end of the installation. Upon arroyo, the screen reveals itself to be a curtain of fine mist, diffusing at its base as the projected text crawls up in an apparition of urgency. To exit the installation, a visitor, with her elongated shadow in tow, must walk through the mist, through Gandhi's words, and into whatever awaits on the other side.

In the reconceptualization of Gandhi's entreaty into a phenomenon that encloses and quite literally touches those who experience Covering Letter, Kallat seeks both to personalize and universalize the communique, transforming it into a message that could have been written "to anyone, anytime, anywhere." Indeed, untethered from its historical moment and the ii individuals responsible for its genesis, the subject field of Covering Letter offers a profound commentary on the here and at present. With its performatively reticent tone, its curtailed and formal structure, and even the fact of its having been typewritten, in ink, on paper, Gandhi'south letter to Hitler is cocky-evidently an object of a bygone era. Yet there is an irony in this. In our new century, textual advice is more prevalent than always. This is the epoch of Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr and those cesspools of cyberspace discourse known equally comments sections, where everyone tin can declare themselves Men of Letters and nearly everyone does. It has never been easier to find a megaphone with which to broadcast 1's "apprehensive opinion." The just challenge, in this new historic period, is being heard above the din.

But it is this very din, this cacophony which passes for communication today, that tends to render Gandhi'southward letter, every bit such, antiquated and foreign. With our newfound technological ability to expound pseudonymously across fiber optic cables, we may fearlessly launch trebuchets from behind the fortresses of our IP addresses and screen-names. Likewise, we tin deny that the targets of our slings and arrows have faces, eyes and hearts whose expressions of injury might crusade us remorse were we actually to behold them. Consequently, our use of words no longer serves to offering or seek elucidation, consolation, or reconciliation. Instead, our words, divorced from meaningful ideas, are reduced to signifiers. In the Internet era, our words have become weapons, embraced, fetishized and exploited without being fully understood, much like the armed services technology that wrought such carnage in the World Wars. Only our words today function likewise equally the lawmaking words, battle cries and war paint of the innumerable factions waging online rhetorical battle with each other and within themselves, at all times, everywhere, near everything.

And to engage in the globe today is to be a partisan in those battles. It is a basic function of social media (and all media accept become social) to create balkanized communities. We have each found our tribe, and if we have non, i surely has found us. For every preference, predilection, philosophy and prejudice, there is a Facebook page, a Reddit category or a collection of Twitter followers waiting to welcome and reinforce our biases. If Gandhi's letter to Hitler was inhaled by a vacuum of ability, then our all-caps, curse-filled rants ricochet around our repeat chambers of crowd-sourced rage, gaining speed as they jettison restraint. Our tribes so go ghettos of grievance, spoiling always for a fight and finding purpose nowhere but in confrontation with the Other. Woe to the virtuous thought, for inevitably information technology will dissolve in bile.

Gandhi's words and his life remind u.s. that nosotros are responsible for angle the moral arc of the universe toward justice, treading its path beyond the horizon and toward whatever awaits on the other side.

One might counter that the kind of fibroid rancor that so dominates the online universe is the domain of crackpots, basement-dwelling malcontents, and a mass of order that has besides much free time or as well little gratuitous time to exercise annihilation productive with information technology. The elites, the thinkers, our leaders, one might affirm, are above such vulgarity. Surely those with their hands on the levers of power grasp, if not the fine art, then at least the value of conscientious communication. We demand look no further than the 2022 presidential election to see that reality tells us otherwise. The nominee of 1 of the two major political parties conducted a campaign whose messaging consisted primarily of outlandish, impulsive tweets and the amplification of toxic slurs from fringe nationalists. The other side's standard bearer attempted to stay to a higher place the fray, but squandered an inordinate corporeality of free energy grappling in the gutter with her opponent, or pandering to unconvinced constituencies with vapid memes and slogans of her own.

Is at that place any hope? Gandhi's case gives us reason to believe there is. As the adage goes, the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice. Though Gandhi'due south letter to Hitler failed abjectly in achieving its stated purpose, the dictator's ultimate aim of establishing a thousand-twelvemonth German empire came to nada while Gandhi's dream of an independent Bharat was realized, in both cases at a tremendous, calamitous human price. Was that justice? The moral universe's arc is perhaps far too long for us e'er to know. Still, as we consider Gandhi'southward words— both in their original context and as the subject of Covering Letter—against today's descent toward the written give-and-take's everyman common denominator, suspicions of a cynical motive on Gandhi's function fall by the wayside. For all of its epistolary modesty, the alphabetic character is if null else, premised upon the humanity of its recipient. Gandhi insistently, stubbornly refused to regard Hitler equally something other than or less than human. With our retrospect, it is easy to regard that insistence every bit frustratingly futile. Simply in this modern era in which the first move in any war of words is to dehumanize our opponents, we can capeesh a moral nobility in Gandhi's insistence on recognizing the humanity in fifty-fifty the worst of humankind, despite its futility. Gandhi's words and his life remind us that nosotros are responsible for bending the moral arc of the universe toward justice, treading its path beyond the horizon and toward any awaits on the other side.

Ajay Raju, a co-founder of The Denizen, is an attorney and philanthropist whose Pamela and Ajay Raju Foundation purchased Roofing Letter for the Philadelphia Museum of Fine art. This column is his response to the prompts in the essay contest the Raju Foundation, The Citizen and 6ABC are launching this week for area high schoolers.

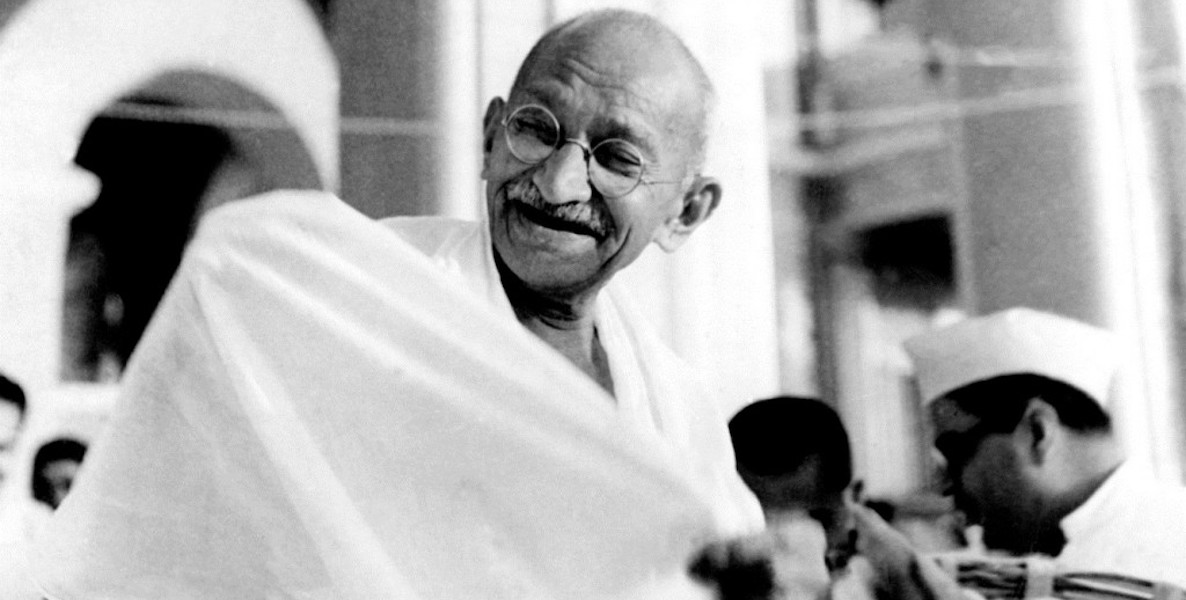

Header photo from Wikimedia Eatables

Source: https://thephiladelphiacitizen.org/gandhis-letter-to-hitler/

0 Response to "The Written Word and the Moral Nobility of Gandhi's Letter to Hitler"

Post a Comment